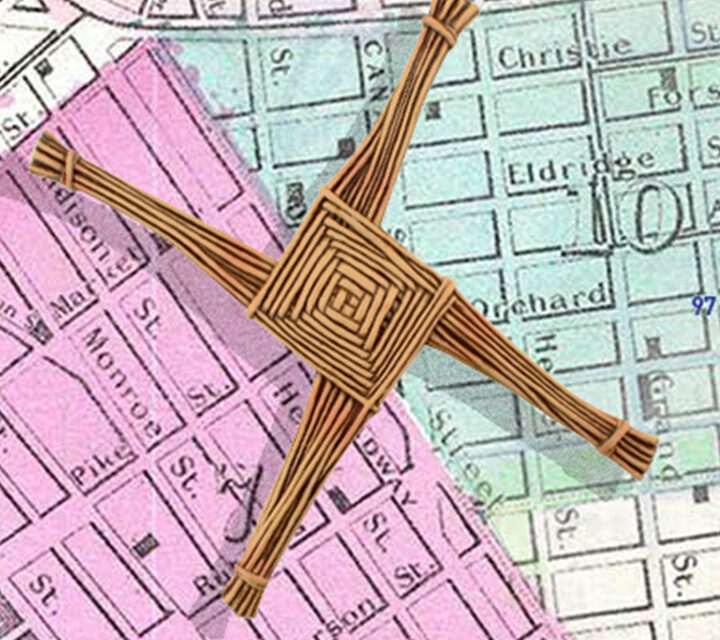

The virtue of decay When built in 1863, the tenement at 97 Orchard Street in the Lower East Side of New York City was considered a hygienic building with outhouses connected to the sewer and a reservoir-fed pump just for residents. But by 1935 it made more sense for the owner to evict the...

Driving east along the Sunrise Highway just before you enter the Hamptons you pass through a portion of the highway that crosses the land of the Shinnecock Nation. There is a large digital pylon for each direction of the highway that someday will advertise their planned casino. The Nation are recognized by the Federal government...

Day two in Long Island, was as enjoyable as it was fast. Yes, fast, everyone is driving 10 mph above the speed limit, and when they see my Massachusetts plates I swear they up it to 15! Before the project start-up meeting and exhibit evaluation at Wertheim National Wildlife Refuge, I visited the observation deck...

Great day for a road trip! Entered Long Island over the Throgs Neck bridge from Queens around 1:00pn.The first destination Oyster Bay on the Sound side of the lower Island. It was clear and cold in the Bay, even the Osprey nests were empty. There was one brave soul on an outboard not far from...

Southie protects their Plovers….we hope. The Shorebird Protection Program is installed for the season at Carson Beach, and local photographer Judy West took photos of our panels at work, informing and evoking love. The panels at Carson are part of a 14-beach rollout of the program in seven languages. The word is out, and if...