During our visit in December to the Auschwitz Birkenau State Museum, a gigantic temporary enclosure was being erected over the iconic entry to Auschwitz II, commonly known as Birkenau, for the 80th anniversary of the camp’s liberation on January 28,1945 by the Ukrainian Front (part of the Red Army). Established as a Museum by the Polish Ministry of Culture and Art in April 1946, former prisoner Tadeusz Wąsowicz and others were authorized to cordon off the site to prevent further removal of camp infrastructure and belongings of the victims. Despite government disinterest in the late 40s and early 50s, erratic funding, and the enormous challenges of maintaining the site, the Museum held its own. Then it thrived partly under the communist government, then even more so when Poland became a democracy in 1989.

With great fortitude, my partner Carol accompanied me on a long-desired trip to this most infamous state museum and historical site in the world. As an interpretive developer and museum designer, I found that the way the museum interpreted this complex subject matter and approached the conservation of a vast array of buildings was a source of professional interest. Carol has contributed to the oversight and development of many of the Content•Designs projects, so there was interest in this for her as well. Content•Design has two related projects in our portfolio, The Armenian Genocide exhibit at the Armenian Museum in Watertown and the design of the Locker of Memory shroud for the victims of the concentration camp Jungfernhof in Latvia. We were not disappointed; this experience was an intersection of evidential storytelling, humanity, land, and architecture.

Visitors are encouraged to sign up for a guided tour; when we arrived on a Wednesday in mid-December, the site appeared near capacity. Upon entering the visitor center, Carol and I passed through security and throngs of people to find the English-speaking guide leading 20 visitors at a time on a schedule. There was no chatting between visitors, our guide had a brisk pace, and her well-practiced script was transmitted through the headsets we were required to wear. She led us through the basement of the visitor center to start our journey, a 375-meter path beginning in a concrete tunnel, past a stone rubble memorial, then up a long incline where the names of the victims are read over loudspeakers embedded into the concrete walls. The effect is eerie.

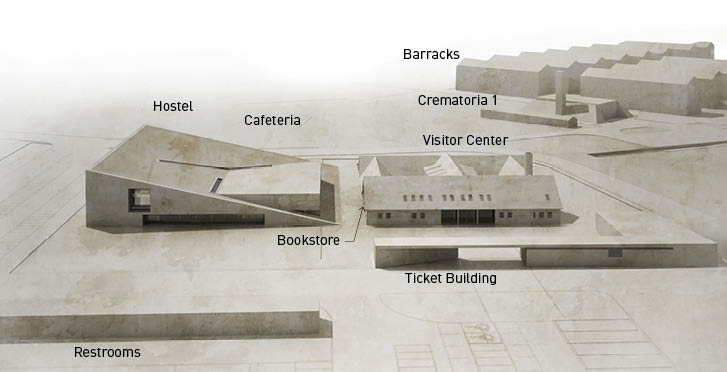

In June, 2023, after seven years of development and construction, the most significant change at the Museum occurred; a new visitor center and entry experience opened to the public. Conceived in 2010 by Kraków based Kozień Architecti and funded by a European Regional Development fund, the project refurbished the existing visitor center, formerly the camp slaughterhouse, added a striking new building, and most importantly, created a disquieting below-grade path from the visitor center to the main camp, Auschwitz 1. The austere design distinguishes itself from the red-tiled clipped box-gabled roofs of the 22 former Polish Army barracks. In the words of the architect, “The Auschwitz-Birkenau camp is a monument, a place-sign. Zone of Silence. The spatial composition of the service area and the entrance to the site should listen to this silence. In silence.”

The adjacent wedge-shaped building houses a hostel and cafeteria. The adjacent wedge-shaped building houses a hostel and cafeteria. Two equally architectonic structures house the ticketing offices and restrooms. Their length and location create distinct lines of flow for the almost 2 million annual visitors, many of whom arrive by tour bus. The museum bus shuttle leaves every 30 minutes from in front of the Cafeteria to Auschwitz 2, Birkenau.

The only drawback to the new visitor center flow is access to the large bookstore—there are two. If you are trying to follow your guide to Birkenau, you have limited time at the bookstore, which has collections marked in numerous language groups. Once you leave the security area, you cannot return to the bookstore.

Visiting Auschwitz 1 requires a moderate level of fitness—in addition to the path described above, the main camp features five two-story barracks that contain the general exhibits. These displayed haunting masses of shoes, suitcases, personal belongings, prostheses, personal items, and, most disturbing of all, human hair. The interpretive graphics communicated clearly, and all were in black and white. They appear to have influenced the graphics at the Holocaust Museum in Washington. There were a few secondary exhibits, such as the exhibit case and label about products manufactured from human hair. In Block 7, we tarried over labels and artifacts and were soon left behind; our guide could still be heard on our headphones outside, but we were soon overtaken by a Polish group. Block 11 did not feature extensive interpretation. The office and latrine are as they were when they were in use. This unfortunate Block is where sentences were given to prisoners, either confinement and torture in the basement cells below or sent to the enclosed yard adjacent where prisoners were shot.

There are also the National exhibits, nine Blocks featuring French, Russian, Slovakian, Austrian, Roma-Sinti, Czech, Hungarian, and Belgian exhibits, plus a newer exhibit designed by the staff at Vad Yashem devoted to the Jewish victims. These exhibits have a wide range of techniques, some more successful than others. For instance, the Hungarian exhibit opened up an entire second floor of their barracks, projected photos onto the wall and created a glass boxcar for visitors to pass through for a cyanic environment. However, the text on glass pedestals was impossible to read, and the black and white images were jumped and hard to distinguish. The Austrian exhibit combined rear-illuminated images of artifacts with actual ones in a wonderfully curated experience. However, the horizontal nature of the artifact case with labels on the back makes it hard for visitors to read. The National exhibits require a second visit, which I made; each one is so different; some provide a greater historical scope than others.

We exited the main camp through the gas chamber/bunker connected to Crematoria 1, which had been restored with the chimney rebuilt from the original bricks and the holes from which the Zyklon B pellets were dropped into the chamber. The dollies and other tools used by the prisoners (Sonderkommando) forced to operate the crematorium were on display. It had been used as a bomb shelter later in the war. Adjacent to the crematorium, our guide pointed out the gallows where the camp commander, Rudolf Höss was hanged after his trial in Poland in 1947. The chamber and crematorium were dark and oppressive. It is the only existing building of this type at Auschwitz; the other four crematoria were destroyed by the Germans before evacuation.

The return trip was through a shorter tunnel, which took us by the headset return station, where our guide informed us to be on the bus to Birkenau in about 20 minutes. Here is where the second bookstore was located. The number of titles incorporating Auschwitz is vast, but the books featured in the bookstore have all been approved by the Museum. You will not find “The Tattooist of Auschwitz” offered due to its historical inaccuracies, but surprisingly, there is a comic book series, which is expertly illustrated and narrated. One of the books I purchased used a “then and now” photo technique with astonishing accuracy. “The Place Where You Are Standing” is based on a photo made by an SS photographer during the arrival and sorting of a transport of Jews from Hungary.

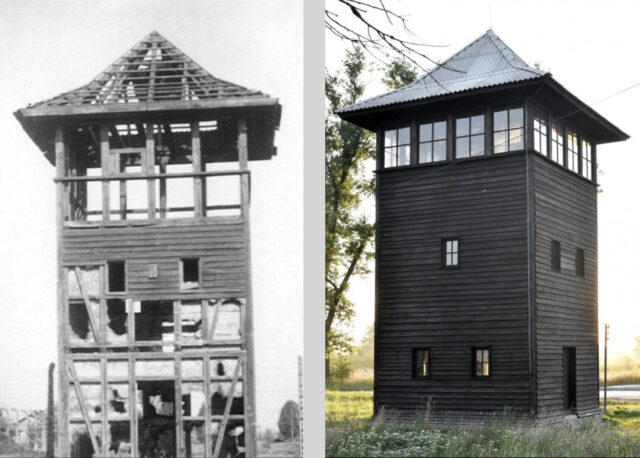

The Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum falls into two categories, a national museum and a historical site. It rivals the Smithsonian in visitation numbers and is spread across 475 acres. As a collecting institution, it is tasked with a seemingly insurmountable curatorial challenge; 100,000 shoes, thousands of suitcases, eyeglasses, prostheses and other personal items requiring attention. The care of the 155 buildings and 300 ruins is equally difficult. While the original Polish Army barracks of Auschwitz 1 are sturdy, the barracks of Birkenau are not so sturdy, and visible supports keep the exterior walls from falling over when tie rods are inadequate. Fabric warehouse-like enclosures cover whole barracks buildings when extensive restoration is required. Guard towers have been rebuilt, and barbed wire replaced. The Museum has acquired practical tools to combat this decay; in 1995, the Museum acquired an autoclave for the pressurized impregnation of wood.

Not only the scale, but the origin of the objects pose emotional challenges. In 2005 many graduates of the Oświęcim vocational school Landmarks Renovation program stopped work cleaning victims shoes when they came to the children’s shoes because they were moved to tears. Conservators at the Museum cannot help but consider the former owner of the dress, pocket watch, shaving brush, or other personal item they are conserving.

The shoe stabilization work consisted of vacuuming, washing, and lightly rubbing with a mixture of white spirit, oil and alcohol to prevent moisture absorption. There are 40 cubic meters of shoes. Fabric Tallisim, the Jewish prayer shawl, are cleaned and protected from light. Suitcases were often made of poor material and were ripped open and searched for valuables. Since the owners were told they were being resettled, their names written on the outside. This is a vital source of information, sometimes infrared reflectography is used to reveal names under paint. But the most controversial collection, 1,850 kilograms (4,075 pounds) of human hair, will be allowed to go gray, out of respect to whom it belonged rather than conserved or buried.

The trip to Birkenau is a 15-minute bus ride; the guides were cordoned off from the visitors at the front of the bus. We exited at a simple driveway and rapidly followed our guide, no headphones, for a quarter mile through sectors B1a and B1b. These two sectors housed 23,000 women in August of 1944, with the total camp population peaking at 90,000 then. Each sector B contained barracks, kitchens, washing, latrine structures, warehouses, and guard buildings. One of our stops was at the embankment alongside the railway where the victims were unloaded, the infamous rail entry to Birkenau visible in the distance. At the guardhouse, the guide gave another short presentation and answered questions. Walking further west, we stopped at the largest sculptural memorial, dedicated in 1967, entitled the "International Monument to the Victims of Fascism." It is an extensive, darkly rambling work that evokes an edgy version of Henry Moore, chairman of the selection committee. There are other memorials, but they are discreet and easily missed. This results from the Museum's memorial policy; crosses and Stars of David are not prominent. At this point, the tour had almost reached the camp's far western end, between the ruins of Crematoria II and III.

The Museum has put much effort into preserving these terrible ruins. Why protect what at first appears to be a pile of bricks? Because the Germans successfully dismantled the crematoria at Treblinka, Belzec, and Sobibor, these remains are significant evidence of the Holocaust. The camp sits on land with a high water table, so water infiltration is essential for below-grade structures like the gas chambers, undressing ramp and other basement rooms in the Crematorium. A concrete wall was inserted around the perimeter of Crematoria II and III to prevent further water damage. Steel supports freeze partially collapsed walls in place while spreading bars to prevent the undressing room walls, which are below grade, from falling in from the force of the earth surrounding them. The work is supported by UNESCO and a private foundation, with the oversight of the head rabbi of Poland.

The monochromatic interpretive panels scattered throughout the site are factual and discreet, and the design has a tombstone. The maps are excellent, with the dimensional representation of the buildings and breaking out the site into quarters, which helps with understanding the complexity of the camp. The content reflects the technical nature of the interpretation. No attempt is made to tell personal stories or camp history on site. These are said in other ways, such as by the anecdotes shared by guides, firsthand accounts published shortly after the war, and comprehensive accounts such as “Auschwitz” by Laurence Rees. I also recommend the award-winning podcast produced by the Museum, “On Auschwitz,” which is highly informative and academic.

The last place I visited was Barrack 13 in Sector B1a. I made my way around a group of French visitors who were focused on the impassioned presentation given by their guide. Upon entering the long, cold, unlit building, the famous children’s wall drawing was on my left, covering a partition wall at the end of a row of large wooden platforms that acted as bunks. It showed a children’s book-style illustration of a parade. This was only created with the approval of the authorities. The subject of this colored wall drawing could only show a topic that does not reflect the horrible reality of the camp.

The Museum has in its collection 2,000 works created by prisoners. The camp had a museum featuring objects looted from prisoners and works created by prisoners. Talented prisoners created Some of these works on demand for the SS officers. Other works were made illegally and contained portraits and the daily chores and brutalities the prisoners were subject to.

The Museum, in its permanent exhibit, preserves the memory of all who passed through its gates by maintaining scrupulous attention to the facts of history. There are no featured heroes and no spotlight on the Sonderkommando uprising in 1944 using commissioned illustrations. All the images used in the exhibits are from photos taken during the era of the camp operation or diagrams to enable an understanding of the camp structure. This is unlike most historical exhibits in the United States, where historical renderings are valued in our interpretive displays.

The Holocaust is subject to misinformation, and the Museum approaches its mission to acquaint as many people as possible with the site's history through an authentic interpretive program. The follow-up email I received from the Museum included links for all social media platforms and three internal online sources, showing the skill with which the Museum uses contemporary digital platforms to extend its message.

Our professional and emotional expectations were exceeded by visiting the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. It is a worthy pilgrimage for all interpretive developers and museum professionals.